“Six years ago I created a series of portraits to remember the faces of the 1916 Easter Rising and mark the then imminent centenary. The revolt was largely centered around the British power base in Dublin but also involved flash points country wide. It spelt the beginning of the end of British rule in Ireland’s south.

The photos available to me were of varied quality, range from to professional portraits to rushed mug shots. I sought to impose a consistent style throughout the collection. I fused both contemporary and classical painting styles to draw together the vastly diverse photographic sources. The unity of style was an attempt underline the diverse nature of the Risings’ protagonists and how they bound together in common purpose.

Before starting I researched each subject’s background to understand better who was looking back at me from each reference photo. The stories I dug up fascinated me on a human level. Most importantly they informed my artistic relationship with the “sitter”, granting me a sliver of insight to their inner workings and motivations.

Here are those back stories now, along with videos from 2016 and links to the finished portraits.” – Rod Coyne.

James Connolly 1868–1916

Born in Edinburgh to Irish immigrant parents, James Connolly was one of the seven signatories of the Proclamation and one of three to sign the surrender. Raised in poverty, his interest in Irish nationalism is said to have stemmed from a Fenian uncle, while his socialist spark came from an impoverished working-class childhood combined with his readings of Karl Marx and others.

James Connolly – Early Years

Connolly first came to Ireland as a member of the British Army. Age 14, he forged documents to enlist to escape poverty and was posted to Cork, Dublin and later the Curragh in Kildare. In Dublin he met Lillie Reynolds and they married in 1890. Despite returning to Scotland, the Irish diaspora in Edinburgh stimulated Connolly’s growing interest in Irish politics in the mid 1890s, leading to his emigration to Dublin in 1896. Here, he founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party.

Connolly spent much of the first decade of the 20th century in America, returning to Ireland to campaign for worker’s rights with James Larkin. Co-founder of the Labour Party in 1912, Connolly would unite Catholic and Protestant colleagues against employers as the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union battled for workers’ rights — strikes which were countered by the employers in the notorious Dublin Lock-out of 1913. Connolly was instrumental in establishing the Citizen Army in 1913 and publicly criticised the Irish Volunteers for inactivity. He opposed conscription, and flew the banner, ‘We serve neither King nor Kaiser, but Ireland’ at Liberty Hall.

James Connolly – 1916

On Easter Monday he led his Citizen Army alongside the Volunteers under Pearse and the wording of the Proclamation is said to be heavily influenced by Connolly’s rhetoric. He served as Commandant-General Dublin Division in the GPO and was badly wounded before the evacuation to Moore Street. James Connolly was executed by a firing squad in Kilmainham Gaol at dawn on May 12, 1916 while strapped to a chair. His final resting place is at Arbour Hill cemetery, Dublin.

James Connolly – Legacy

In Dublin there is a statue of Connolly outside Liberty Hall and others in New York and Chicago, a measure of his international influence. Connolly Station, one of the main railway stations in Dublin and a hospital in Blanchardstown are also named in his honour. In a 1972 interview on the Dick Cavett Show, John Lennon stated that James Connolly was an inspiration for his song, “Woman Is the Nigger of the World”. Lennon quoted Connolly’s ‘the female is the slave of the slave’ in explaining the feminist inspiration for the song.

View James Connolly’s finished portrait here.

.

.

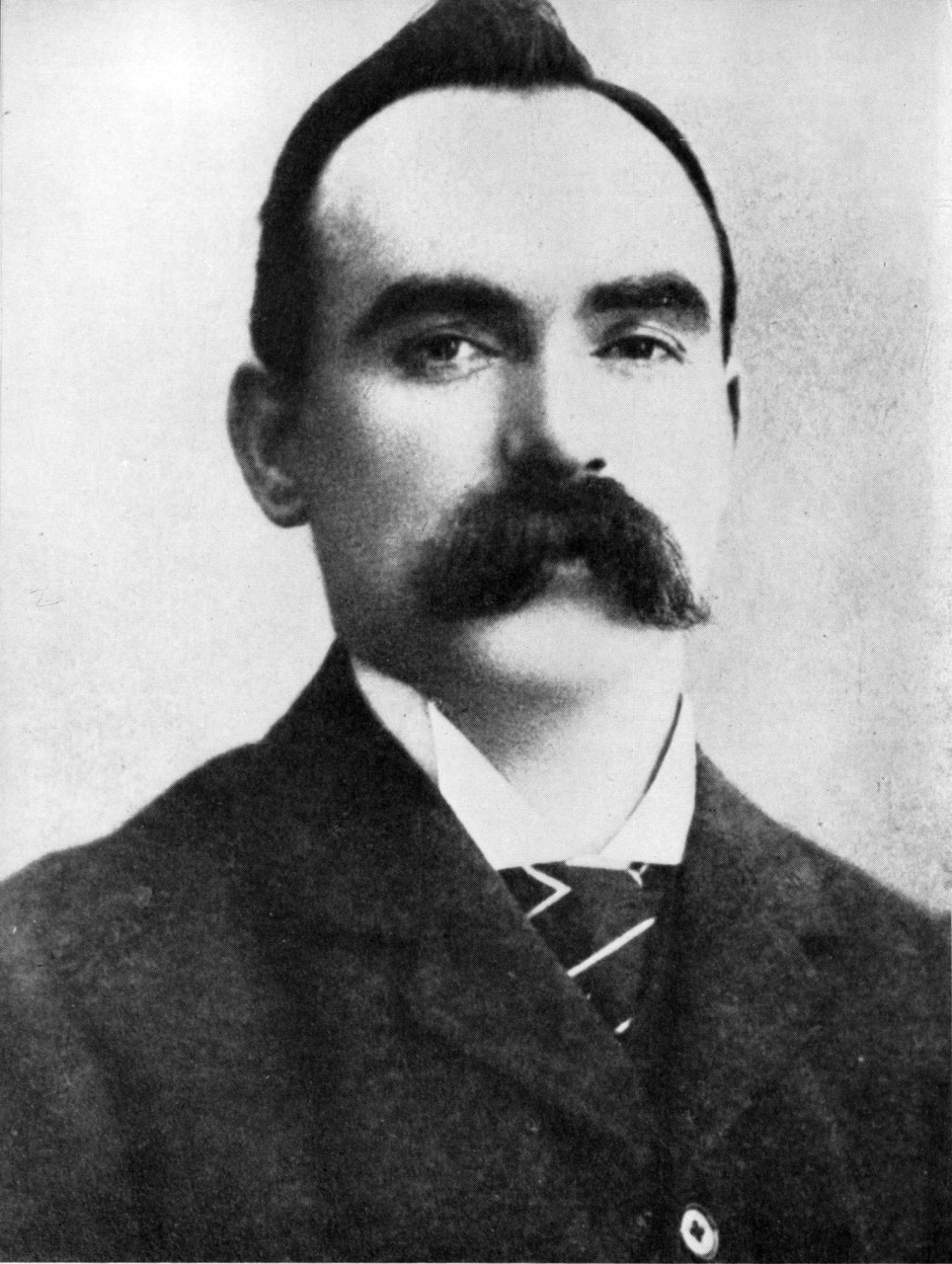

Thomas Clarke 1858-1916

Thomas Clarke – Early Years

Thomas Clarke was born on the Isle of Wight to Irish parents, his father was a sergeant in the British army who was stationed there. The family moved to South Africa and later to Dungannon, Co Tyrone, where Clarke grew up from about the age of seven, attending Saint Patrick’s national school.

In 1882, he emigrated to American. During his time there he joined the republican organisation Clan na Gael and, as a proponent of violent revolution, he would serve 15 years in British jails for his role in a bombing campaign in London.

Thomas Clarke – Road to Revolution

Clarke was released in 1898, and spent nine more years in America. He returned to Dublin in 1907 setting up a tobacconist’s shop on Great Britain Street (now Parnell Square), before being co-opted onto the IRB Military Council which was responsible for planning the Easter Rising.

Because of his criminal convictions, Clarke maintained a low profile in Ireland, but was influential behind the scenes in the years of preparation for the Rising. With Denis McCullough, Bulmer Hobson and Seán Mac Diarmada, Clarke revitalised the IRB and had a major role in setting up the Irish Freedom newspaper.

Devoted to the formation of an Irish republic, Clarke was also Chairman and a Trustee of the Wolfe Tone Memorial Committee, which organised the first pilgrimage to his grave at Bodenstown, Co Kildare in 1911.

The first signatory of the Proclamation of Independence because of his seniority and commitment to the cause of Irish independence, Clarke was with the group that occupied the GPO. He opposed the surrender, but was outvoted.

Thomas Clarke – Remembered

He was married to Kathleen Daly, niece of the veteran Fenian John Daly, and had three children.

In 1922, a collection of his prison writings, Glimpses of an Irish Felon’s Prison Life, was published.

Clarke wrote: “Clinch your teeth hard and never say die. Keep your thoughts off yourself all you can.”

He faced the firing squad at Kilmainham Gaol on May 3, 1916, age 59.

Before its demolition in 2008, a tower in Ballymun, Dublin, and a railway station in Dundalk, Co Louth, were named after Clarke.

View Thomas Clarke’s finished portrait here.

.

The O’Rahilly 1875-1916

Michael Joseph O’Rahilly (Irish: Mícheál Seosamh Ó Rathaille or Ua Rathghaille); (22 April 1875 –29 April 1916) known as The O’Rahilly, was an Irish republican and nationalist; he was a founding member of the Irish Volunteers in 1913 and served as Director of Arms. Despite opposing the action, he took part in the Easter Rising in Dublin and was killed in a charge on a British machine gun post covering the retreat from the GPO during the fighting.

Early life

Born in Ballylongford, County Kerry, O’Rahilly was educated in Clongowes Wood College (1890-3). As an adult, he became a republican and a language enthusiast. He joined the Gaelic League and became a member of An Coiste Gnotha, its governing body. He was well travelled, spending at least a decade in the United States and in Europe before settling in Dublin.

O’Rahilly was a founding member of the Irish Volunteers in 1913, who organized to work for Irish independence and resist the proposed Home Rule; he served as the IV Director of Arms. He personally directed the first major arming of the Irish Volunteers, the landing of 900 Mausers at the Howth gun-running on 26 July 1914.

The Irish Volunteers

O’Rahilly was not party to the plans for the Easter Rising, nor was he a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), but he was one of the main people who trained the Irish Volunteers for the coming fight. The planners of the Rising went to great lengths to prevent those leaders of the Volunteers who were opposed to unprovoked, unilateral action from learning that a rising was imminent, including its Chief-of-Staff Eoin MacNeill, Bulmer Hobson, and O’Rahilly.

O’Rahilly took instructions from MacNeill and spent the night driving throughout the country, informing Volunteer leaders in Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, and Limerick that they were not to mobilise their forces for planned manoeuvres on Sunday.

Easter Rising

Arriving home, he learned that the Rising was about to begin in Dublin on the next day, Easter Monday, 24 April 1916. Despite his efforts to prevent such action (which he felt could only lead to defeat), he set out to Liberty Hall to join Pearse, James Connolly, Thomas MacDonagh, Tom Clarke, Joseph Plunkett, Countess Markievicz, Sean Mac Diarmada, Eamonn Ceannt and their Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army troops. Arriving in his De Dion-Bouton motorcar, he gave one of the most quoted lines of the rising – “Well, I’ve helped to wind up the clock — I might as well hear it strike!” Another famous, if less quoted line, was his comment to Markievicz, “It is madness, but it is glorious madness.”

He fought with the GPO garrison during Easter Week. On Friday 28 April, with the GPO on fire, O’Rahilly volunteered to lead a party of men along a route to Williams and Woods, a factory on Great Britain Street (now Parnell Street). A British machine-gun at the intersection of Great Britain and Moore streets cut him and several of the others down. O’Rahilly slumped into a doorway on Moore Street, wounded and bleeding badly but, hearing the English marking his position, made a dash across the road to find shelter in Sackville Lane (now O’Rahilly Parade). He was wounded diagonally from shoulder to hip by sustained fire from the machine-gunner.

Desmond Ryan’s The Rising maintains that it “was 2.30pm when Miss O’Farrell reached Moore Street, and as she passed Sackville Lane again, she saw O’Rahilly’s corpse lying a few yards up the laneway, his feet against a stone stairway in front of a house, his head towards the street.”

The memorial in O’Rahilly Parade, Dublin.

O’Rahilly wrote a message to his wife on the back of a letter he had received in the GPO from his son. Shane Cullen etched this last message to Nannie O’Rahilly into his limestone and bronze memorial sculpture to The O’Rahilly. The text reads:

‘Written after I was shot. Darling Nancy I was shot leading a rush up Moore Street and took refuge in a doorway. While I was there I heard the men pointing out where I was and made a bolt for the laneway I am in now. I got more [than] one bullet I think. Tons and tons of love dearie to you and the boys and to Nell and Anna. It was a good fight anyhow. Please deliver this to Nannie O’ Rahilly, 40 Herbert Park, Dublin. Goodbye Darling.’

Source of name

In Gaelic tradition, chief of clans were called by their clan name preceded by the determinate article, for example Robert The Bruce. O’Rahilly’s calling himself “The O’Rahilly” was purely his own idea. In 1938, the poet William Butler Yeats defended O’Rahilly on this point in his poem The O’Rahilly.