“Six years ago I created a series of portraits to remember the faces of the 1916 Easter Rising and mark the then imminent centenary. The revolt was largely centered around the British power base in Dublin but also involved flash points country wide. It spelt the beginning of the end of British rule in Ireland’s south.

The photos available to me were of varied quality, range from to professional portraits to rushed mug shots. I sought to impose a consistent style throughout the collection. I fused both contemporary and classical painting styles to draw together the vastly diverse photographic sources. The unity of style was an attempt underline the diverse nature of the Risings’ protagonists and how they bound together in common purpose.

Before starting I researched each subject’s background to understand better who was looking back at me from each reference photo. The stories I dug up fascinated me on a human level. Most importantly they informed my artistic relationship with the “sitter”, granting me a sliver of insight to their inner workings and motivations.

Here are those back stories now, along with videos from 2016 and links to the finished portraits.” – Rod Coyne.

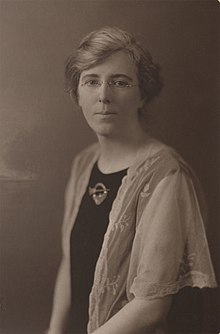

Margaret Skinnider – Schoolteacher turned Sniper

Margaret Skinnider (28 May 1892 – 10 October 1971) was a revolutionary and feminist born in Coatbridge, Scotland. She fought during the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin. Her part in the Easter Rising was all the more notable because she was a woman, a sniper and the only female wounded in the action. She was mentioned three times for bravery in the dispatches sent to the Dublin GPO. Sadhbh Walsche in The New York Times refers to her as “the schoolteacher turned sniper.”

Margaret Skinnider – Rebel Roots

Margaret Skinnider was born to Irish parents in Coatbridge, North Lanarkshire, in 1893. She trained as a mathematics teacher and joined Countess Markievicz’s organization Cumann na mBan in Glasgow. In 1915 the Countess asked Skinnider to smuggle detonators and bomb-making equipment into Ireland in preparation for the planned Easter Rising in Dublin the following year. She arrived in Dublin a week before the rebellion and lodged with Markievicz.

Margaret Skinnider – in the Line of Fire

When the Rising broke out on Easter Monday 1916, Skinnider took up her position as a sniper on the roof of the College of Surgeons, on St Stephens’ Green, Dublin. Margaret was an excellent marks-woman, having learned to shoot in a rifle club which, ironically, had been set up so that women could help in defence of the British Empire.

“It was dark there, full of smoke and the din of firing, but it was good to be in action . . . more than once I saw the man I aimed at fall”

On Wednesday 26th April she was shot three times when attempting to burn down houses in Harcourt Street.

“It took only a few moments to reach the building we were to set afire. Councillor [William] Partridge smashed the glass door in the front of a shop that occupied the ground floor. He did it with the butt of his rifle and a flash followed. It had been discharged! I rushed past him into the doorway of the shop, calling to the others to come on. Behind me came the sound of a volley and I fell. It was as I had on the instant divined. The flash had revealed us to the enemy. ‘It’s all over,’ I muttered, as I felt myself falling. But a moment later, when I knew I was not dead, I was sure I should pull through…

They laid me on a large table and cut away the coat of my fine, new uniform. I cried over that. Then they found I had been shot in three places, my right side under my arm, my right arm, and in the back of my right side… They had to probe several times to get the bullets, and all the while Madam held my hand. But the probing did not hurt as much as she expected it would. My disappointment at not being able to bomb the Shelbourne Hotel was what made me unhappy…”

She was brought to St Vincent’s Hospital where she was arrested and held in the Bridewell Police Station. She was interrogated until a surgeon from the hospital contacted the British authorities in Dublin Castle and said she was unfit for imprisonment.

She spent many weeks in hospital, and on her release, managed to obtain a permit to travel back to Scotland. Skinnider stayed in Glasgow until August 1916 when she returned briefly to Ireland, but quickly fled to America for fear of being caught and imprisoned. While in America she collected funds and set out on a lecture tour raising awareness of the fight for Irish Independence. During this time, she also published her autobiography Doing My Bit for Ireland.

Margaret Skinnider – Beyond 1916

Skinnider returned to Ireland in 1917 and took up a teaching position in North Dublin, but she did not give up on her revolutionary ideals. She was active during the War of Independence of 1920/21 and was arrested and imprisoned. During the Civil War that followed, she became Paymaster General of the Provisional Irish Republican Army. She was arrested again in 1923 and held at the North Dublin Union.

After her release, she worked as a teacher at a Primary School in Dublin until she retired in 1961. She was also a prominent member of the Irish National School Teachers’ Association for many years.

Margaret Skinnider lived for many years in Glenageary, County Dublin, and died in October 1971. She is buried in the Republican plot in Glasnevin Cemetery.

View Margaret Skinnider’s finished portrait here.

Countess Markievicz 1868-1927

The famous Irish revolutionary known as Countess Markievicz was born Constance Gore-Booth in 1868. She was born in London to Sir Henry Gore-Booth, the famous arctic explorer. As an Anglo-Irish landlord, her father was not typical of his type and administered his lands with a degree of compassion for the peasantry who farmed it.

Find out more about Rod Coyne’s “1916 Portrait Collection” premier here.

Countess Markievicz – Aristocrat to Rebel

Constance initially studied painting in London in 1893 where she became involved in the issue of suffrage for women, joining the ‘National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies’. She continued her artistic studies in Paris in 1898 where she met Count Markiewicz, who was a Ukrainian aristocrat of Polish origin. They wed in 1901 after which she assumed the title Countess Markievicz. The couple settled in Dublin in 1903 where the Countess co-founded the ‘United Artists Club’ which was a cultural and artistic organisation. It was perhaps inevitable that while circulating in such society she would be exposed to the revolutionary ideas that were being swept along with the Gaelic revival of the time. In 1908 she joined Sinn Fein and Inghinidhe na hEireann – ‘The Daughters of Ireland’, which was a revolutionary group established by Maud Gonne, with whom she later acted at the fledgling Abbey Theatre. She continued to participate in the Suffragette movement in England and by standing for election she helped to defeat Winston Churchill in a 1908 Manchester by-election.

In 1909 she established the radical ‘Fianna Eireann’ which was aimed at instructing a youth army in the use of firearms. She was jailed by the British authorities in 1913 after speaking at an IRB rally to protest the visit of George V to Dublin. She had also joined the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) established by James Connolly in response to the 1913 ‘lockout’ of workers. She established soup kitchens and aid for the Dublin poor, often using her own funds. Her marriage had by now disintegrated with her husband returning to Europe in 1913.

Countess Markievicz – Frontline 1916

As a Lieutenant in the ICA the Countess participated in the Easter Rising of 1916 where she was second-in-command at the fight on St. Stephens Green. Under the command of fellow ICA member Michael Mallin they occupied the Royal College of Surgeons, rebelling for a total of 6 days. The Countess was jailed in Kilmainham and sentenced to death but her sentence was commuted on grounds of her gender. ‘I do wish your lot had the decency to shoot me’ she retorted. She was released from prison in 1917 by which time the tide of support had turned in favour of the rebels and the path to independence was set.

In 1918 she was again jailed for her anti-conscription campaigning but upon release was elected to the English parliament, refusing to take her seat. She was the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons. She was a member of the first ‘Dail’ (Irish Parliament) in 1919 and became the first Irish (and indeed European) Cabinet Minister, serving as Minister for Labour from 1919 to 1922.

Countess Markievicz – Fledgling Free State

She joined DeValera in opposition to the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1922 which partitioned the country and fought in Dublin in the ensuing civil war. She was again imprisoned but this time by her former comrades-in-arms. Upon her release she became a founder member of Fianna Fail and was elected to the fifth Dail in 1927. DeValera had by this time changed tactics and intended to participate in the parliament. The Countess however, never got her chance when, at the age of 59, she died of tuberculosis (or possibly appendicitis) in July of 1927. She likely caught the disease while working in the Dublin slums. Her husband and family were by her side.

She was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, the final resting place of so many Irish patriots with a farewell crowd of 300,000 in attendance.

View Countess Markievicz’s finished portrait here.

.

Kathleen Clarke 1878-1972

Kathleen Clarke was born in Limerick to Edward and Catharine Daly on 11 April 1878. She was the third daughter in a family of nine girls and one boy, Edward junior (Ned), born in 1890, five months after the death of his father. Edward senior, along with his brother John, had been involved with the Fenian uprising of 1867, and had spent some time in prison.

Kathleen Clarke – Rebel Roots

The family was left in poor circumstances following Edward’s death, but was rescued by another Daly brother, James, who had emigrated in the 1850s and become very wealthy. He helped the family until John Daly returned in 1896. John had spent 12 years in prison in England for involvement in a Fenian dynamite campaign, and came back to Limerick a hero. He established a bakery in William Street, where several of his nieces worked. Kathleen refused to join them, as she had established a very successful dressmaking business. In prison, John had become close friends with Tom Clarke, who was serving 15 years for dynamite activities. When Tom was released in 1898, he visited his old friend in Limerick, and he and Kathleen Daly fell in love. At the time she was 20 and he was 40. They were married in New York in 1901 and their first child, John Daly Clarke, was born on 13 June 1902. Tom worked for John Devoy and the American Fenian group, Clan na Gael.

Kathleen Clarke – and Tom Clarke

By 1907, Tom was aware of the possibility of a European war, along with a rising mood of nationalism in Ireland. He sensed an opportunity to strike a blow against England, so he and Kathleen returned to Ireland that year. Tom became a tobacconist and newsagent in Amiens Street, Dublin, later opening a second shop in Parnell Street. Supported by Clan na Gael, he established a circle of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), and his little shop became a centre of republican activity and plotting, watched all the time by police detectives. He and Kathleen had two more sons, Tom, born in 1908, and Emmet, born in 1909. Tom was also involved in the establishment of the Irish Volunteers in late 1913 and Kathleen’s brother Ned was one of the first to join, ultimately becoming Commandant of the First Battalion at the age of 23. Kathleen was active as a founder member of Cumann na mBan, and worked hard at fundraising as well as in her domestic and shopkeeping responsibilities. The First World War began in 1914, and the IRB knew their opportunity was coming, but it was Easter 1916 before their plans came to fruition. Kathleen was apparently sworn into the IRB beforehand, so that she would have enough information to carry on the struggle for independence if the Rising was a failure.

After the week-long fighting and the surrender, Kathleen was taken to visit her husband in Kilmainham Jail the night before his execution. The interview lasted almost two hours, then Kathleen had to leave; Tom was shot in the early morning on 3 May. The following night she was back in the jail, with two of her sisters, to say goodbye to their brother Ned; he was executed on 4 May. Kathleen was expecting another child, but did not tell her husband in their last interview. She fell seriously ill shortly afterwards, exhausted by her work establishing a fund for Volunteer dependants, and lost the baby.

Kathleen Clarke – Beyond 1916

Kathleen remained active in Cumann na mBan, and with the dependants’ fund, for several years; her sons went to school in Limerick, and were cared for by their aunts. In May 1918 she was arrested because of an alleged ‘German plot’, and spent nine months in Holloway Jail in London along with Constance Markievicz and Maud Gonne. She was finally released after a heart attack. Kathleen was elected to Dublin Corporation for Sinn Féin, and when the first, illegal, Dáil Eireann was established, she acted as a judge in the Republican Courts. During the War of Independence, she was active as a courier, smuggling money and weapons to the IRA. By the time the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in 1921, Kathleen was a TD, and was among those who vehemently opposed the Treaty. She took the anti-Treaty side during the subsequent Civil War, but eventually accepted the Free State. In 1924 she made a lecture tour of the USA, fundraising for the dependants’ fund. In 1926 Kathleen became a founder member of Eamon de Valera’s new political party, Fianna Fáil; she was a member of the Senate between 1926 and 1928, and later a TD again. Kathleen Clarke was always a somewhat detached member of Fianna Fail, and did not hesitate to speak her mind if she disagreed with party policy. In 1937, she was one of several women TDs who took issue with de Valera’s new Constitution because of its anti-woman attitudes. She remained a member of Dublin Corporation until 1945 and had the distinction of becoming Dublin’s first woman Lord Mayor in 1939, serving two terms before retiring in 1941 on the grounds of ill-health. She resigned from Fianna Fáil in 1943, no longer in sympathy with the party, and stood unsuccessfully for Sean MacBride’s Clann na Poblachta party in 1948. Thereafter she retired from politics. Active on numerous boards and committees, including the National Graves Association, Kathleen lived for some time in Sandymount with her son John Daly, but in 1965 moved to Liverpool to live with her son Emmet, who had two sons, her only grandchildren. Here she died on 29 September 1972, aged 94. She was given a State funeral in Dublin and is buried in Dean’s Grange Cemetery.